The heart and soul of the AAVSO are our observers - a diverse collection of people from around the globe who share a common interest in what we do. When asked what motivates them, this is what they had to say...

Franz-Josef (Josch) Hambsch (HMB)

I have been interested in astronomy from my childhood more than 45 y ago, when I received my first book with a photographic sky atlas. At the age of 18 I bought my first 4.25“ Newtonian from a department store, which I use from an attic of the apartment in the city where I lived at that time. A few years later, I stepped up to a orange colored C8 that I used for many years visually until I got my own observatory in our backyard about 15 y ago, where I first started out to use a CCD camera to take pretty pictures on a 16“ scope. But being a scientist, I turned after a couple of years towards the more scientific part of the hobby in observing variable stars. In this field amateur astronomers can still contribute to the advancement of science. I have been intensifying my observations in the past years by having now a remote robotic observatory under pristine skies. My main interest is in observations of cataclysmic variables (CVs) and RR Lyr stars. I participate in several collaborations like Center for Backyard Astrophysics (CBA) and VSNET (Kato et al., Kyoto University) as well as with professional astronomers. Many results where I contribute with photometric observations have been published in refereed journals. In the meantime, I submitted nearly 1.5 million observations to the AAVSO database. Although I observe mainly using digital techniques, each time I look up to the sky and think about the stars, I feel how tiny we are in the vast universe and that we should have always in mind that we live on a small planet called Earth we should pamper much more than we do now.

I have been interested in astronomy from my childhood more than 45 y ago, when I received my first book with a photographic sky atlas. At the age of 18 I bought my first 4.25“ Newtonian from a department store, which I use from an attic of the apartment in the city where I lived at that time. A few years later, I stepped up to a orange colored C8 that I used for many years visually until I got my own observatory in our backyard about 15 y ago, where I first started out to use a CCD camera to take pretty pictures on a 16“ scope. But being a scientist, I turned after a couple of years towards the more scientific part of the hobby in observing variable stars. In this field amateur astronomers can still contribute to the advancement of science. I have been intensifying my observations in the past years by having now a remote robotic observatory under pristine skies. My main interest is in observations of cataclysmic variables (CVs) and RR Lyr stars. I participate in several collaborations like Center for Backyard Astrophysics (CBA) and VSNET (Kato et al., Kyoto University) as well as with professional astronomers. Many results where I contribute with photometric observations have been published in refereed journals. In the meantime, I submitted nearly 1.5 million observations to the AAVSO database. Although I observe mainly using digital techniques, each time I look up to the sky and think about the stars, I feel how tiny we are in the vast universe and that we should have always in mind that we live on a small planet called Earth we should pamper much more than we do now.

Kristine Larsen (LKR)

Why do I observe? Because it brings me moments of peace in an otherwise hectic day, and brings me closer to the universe. I keep it local during the day and observe sunspots, but at night I prefer deep sky objects. Being able to directly experience photons from those faint fuzzies brings me a particular kind of joy. I also love checking out variable stars – you never know what they’re going to do next!

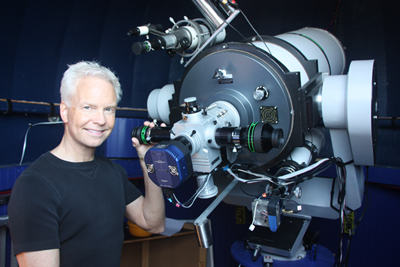

Mario Motta, MD (MMX)

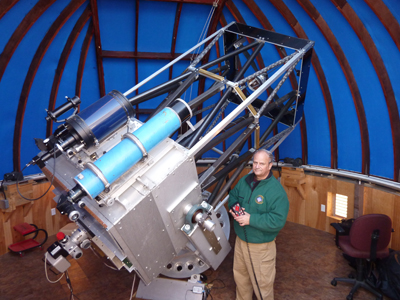

I have been an astronomer my entire life, and at one point was planning a career in astrophysics, but.. I ended up in medicine as a cardiologist. I have never lost my intense passion for astronomy however, and I have been observing, imaging, and doing research now for more than 50 years. Given that my parents were immigrants, they could not afford the “ large telescope” that I secretly wanted; they did give me a small refractor at age 7 that started my love affair with astronomy. This was a blessing in disguise however as I therefore resolved to build my own telescopes, and learned to grind telescope mirrors and make my own parts. I made my first telescope at age 14, an 8 inch f7, which I used for a number of years. After medical school was completed, I wanted to get back into observing, and built a 16 inch, then a 32 inch, and finally more recently built my latest, a 32 inch f6 ‘relay” telescope, every part handmade. In the past I had built several backyard observatories. In 2004, with our latest move, I took the opportunity to build the observatory as an integral part of our new home. With this observatory and telescope I greatly enjoy all aspects of amateur astronomy, from community outreach, to teaching, to research with AAVSO and transit teams, and of course just observing for the shear thrill of it. I especially like to do targets of opportunity, such as supernova searches, transits, and gamma ray bursts. After all these years, I still greatly enjoy this activity, and look forward to a lifetime of observing and research. In what other field can you collect data and have such great fun doing it?

I have been an astronomer my entire life, and at one point was planning a career in astrophysics, but.. I ended up in medicine as a cardiologist. I have never lost my intense passion for astronomy however, and I have been observing, imaging, and doing research now for more than 50 years. Given that my parents were immigrants, they could not afford the “ large telescope” that I secretly wanted; they did give me a small refractor at age 7 that started my love affair with astronomy. This was a blessing in disguise however as I therefore resolved to build my own telescopes, and learned to grind telescope mirrors and make my own parts. I made my first telescope at age 14, an 8 inch f7, which I used for a number of years. After medical school was completed, I wanted to get back into observing, and built a 16 inch, then a 32 inch, and finally more recently built my latest, a 32 inch f6 ‘relay” telescope, every part handmade. In the past I had built several backyard observatories. In 2004, with our latest move, I took the opportunity to build the observatory as an integral part of our new home. With this observatory and telescope I greatly enjoy all aspects of amateur astronomy, from community outreach, to teaching, to research with AAVSO and transit teams, and of course just observing for the shear thrill of it. I especially like to do targets of opportunity, such as supernova searches, transits, and gamma ray bursts. After all these years, I still greatly enjoy this activity, and look forward to a lifetime of observing and research. In what other field can you collect data and have such great fun doing it?

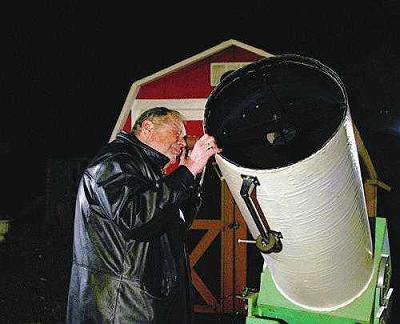

Bob Buchheim (BHU)

The attached picture shows me in my backyard observatory, but the photo that I really wish I still had was the one showing me and Mike Conley, both of us in the fourth grade, proudly standing with our telescopes. His was a 3-inch Edmund reflector, mine a 2.5-inch Sears refractor. The occasion was the classroom “show and tell”, and Mike took center stage when he used the blackboard to explain how a reflecting telescope works. The equatorial mount was a bit mysterious to both of us, so he skipped over that part. Together, we discovered the craters on the Moon and the rings of Saturn, and we watched a meteor shower from his backyard (probably the Perseids, since it was a warm night).

The attached picture shows me in my backyard observatory, but the photo that I really wish I still had was the one showing me and Mike Conley, both of us in the fourth grade, proudly standing with our telescopes. His was a 3-inch Edmund reflector, mine a 2.5-inch Sears refractor. The occasion was the classroom “show and tell”, and Mike took center stage when he used the blackboard to explain how a reflecting telescope works. The equatorial mount was a bit mysterious to both of us, so he skipped over that part. Together, we discovered the craters on the Moon and the rings of Saturn, and we watched a meteor shower from his backyard (probably the Perseids, since it was a warm night).

About 40 years and four or five telescopes later, John Hoot and Russ Sipe introduced me to the idea that backyard astronomers with modest instruments can conduct scientifically-useful observations, such as asteroid lightcurves, occultation timings, and variable star photometry. They also introduced me to the community of backyard scientists, including the AAVSO and the essential role that it plays in bringing amateur observers and professional researchers together. I am awed by the beauty of the universe, the privilege of seeing (and measuring) objects and phenomena that still contain mysteries, and the opportunity to live my childhood dream of being an astronomer.

Tessa Hiscox (HTCA)

Astronomy is so important for us all. It gives us our place is the universe and allows us to marvel not only at the beauty of the universe, but how it works. Astronomy gives us a wider understanding of our own world and everyday lives.

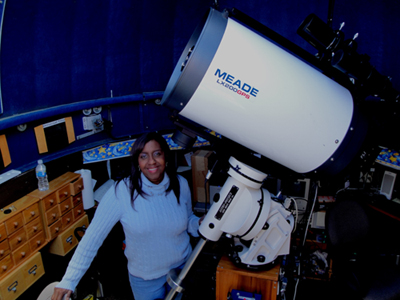

Barbara Harris (HBB)

I have had a fascination with astronomy since high school. I learned about Greek myths and the constellations that were associated with those myths while a sophomore in high school. Every time I learned about a myth, I would want to look up at the night sky and find the constellation associated with that myth. Around the same time, I took high school physics and learned about the physical properties of the stars and the universe. One of the most fascinating concepts I learned about stars was the fact that we are seeing them in the past. I was captivated by the fact that the universe was so vast and the stars so distant that we are seeing them as they were many years ago.

I have had a fascination with astronomy since high school. I learned about Greek myths and the constellations that were associated with those myths while a sophomore in high school. Every time I learned about a myth, I would want to look up at the night sky and find the constellation associated with that myth. Around the same time, I took high school physics and learned about the physical properties of the stars and the universe. One of the most fascinating concepts I learned about stars was the fact that we are seeing them in the past. I was captivated by the fact that the universe was so vast and the stars so distant that we are seeing them as they were many years ago.

As I learned more astronomy, I loved the splendor of the night sky but I wanted more from the night sky. I started to learn about individual stars and the fact that each star has its own story to tell. This led me to variable star photometry. By observing variable stars I can determine the story each star is trying to tell. I love sharing the night sky with people who never look up. I like pointing out that although they see many stars in the sky and see them as a collective group of stars, I point out individual stars and introduce those stars by name and give a little bio of those stars.

I love taking CCD images of star fields. It is exciting to download the image and determine what is going on with a particular star at a particular time. I am always fascinated by the fact that the universe is so large and there are so many stars that at that particular moment I may be the only person in the whole world who is paying attention to that particular star.

Mati Morel (MMAT)

Looking back, the way in which astronomical objects were organized, classified and arranged struck a chord with me from a young age. Entry to Variable Stars was a "natural". But, it is more than that, I think I always wanted to know how I fitted into the "big picture", the whole scheme of things.

Looking back, the way in which astronomical objects were organized, classified and arranged struck a chord with me from a young age. Entry to Variable Stars was a "natural". But, it is more than that, I think I always wanted to know how I fitted into the "big picture", the whole scheme of things.

My revelation came in 1970/71, as to what it was with astronomy (or other scientific disciplines, for that matter) that gave me a buzz - the thrill of discovery. I was assigned to an exploration party in the backblocks of Western Australia, searching for deposits of metal ores. I felt the same sense of being part of a possible new discovery. That's been an ongoing theme with me ever since.

With a natural inclination to pursue things doggedly, it may be not surprising that I became the chief producer of charts, working with Dr. Frank Bateson of the VSS, RASNZ for about three decades, producing about 1000 charts for the Section. I've worked with other eminent authorities on other projects in the last 10-15 years, the likes of Bill Liller, Brian Skiff etc., then branched into producing my own charts of deep-sky objects in the 1980s and 1990s.

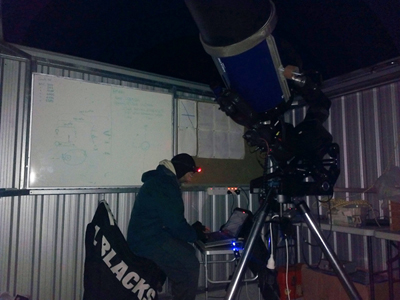

Robert Jenkins (JRBA)

There must be something special about doing something that necessitates that you sit in a shed, open to the night sky, wiping icicles of your sleeve on a cold night or swatting the mosquitoes on a hot night. But that is astronomy and especially variable star research. Why do we do it? For me it is the thrill of doing work that could help unlock the secrets of our Universe. The thought that you are doing real science from your own backyard. The thrill that you have a good chance of seeing something that no one else has seen. And the serenity of looking up and seeing light that has taken an eternity to reach you. A most spiritual experience.

There must be something special about doing something that necessitates that you sit in a shed, open to the night sky, wiping icicles of your sleeve on a cold night or swatting the mosquitoes on a hot night. But that is astronomy and especially variable star research. Why do we do it? For me it is the thrill of doing work that could help unlock the secrets of our Universe. The thought that you are doing real science from your own backyard. The thrill that you have a good chance of seeing something that no one else has seen. And the serenity of looking up and seeing light that has taken an eternity to reach you. A most spiritual experience.

Gary Walker (WGR)

I am proud to have been the first amateur to submit CCD Observations to the AAVSO and currently have over 65,000 variable star observations pursuing research in this field. I am most happy when making observations.

I am proud to have been the first amateur to submit CCD Observations to the AAVSO and currently have over 65,000 variable star observations pursuing research in this field. I am most happy when making observations.

Santanu Basu (BSAB)

I have liked astronomy since my childhood. At that time, I had no knowledge of astronomical objects. After I grew up, I came to know more about astronomy.

I have liked astronomy since my childhood. At that time, I had no knowledge of astronomical objects. After I grew up, I came to know more about astronomy.

I had no telescope, but I observed the sky with my open eyes. After some years, I collected the optical kits and assembled it with the help of a senior member of the Kolkata Sky Watchers Association and started to observe sunspots and sometimes the night sky. I observe the motion of sunspots, their groups and how they change, etc.

Now I have a 4-inch Newtonian reflecting telescope. I think, in future, if I am able to buy a larger telescope then it will be better for me to observe the Sun in more detail.

I like our Sun, and like our universe, so if I get more opportunity, I shall do more observation.

Roger Kolman (KRS)

“Let there be light.”

With this statement, we see the Big Bang. All of the energy in the Universe was created at that moment. It can be neither created nor destroyed, but may change form among many processes, including the creation of photons, the units of light.

As a youngster, I began observing the planets, the Messier objects and the brighter NGC objects as “pretty fuzzies” that introduced me to the beauty of the Universe.

In 1961 I read an article in Sky & Telescope by Clint Ford entitled “Sidelights on Observing Variable Stars”. To think that one could use the photons that arrived through a tortuous route to MY eye to do work of scientific value just blew me away.

I have been a visual observer for the past 53 years using the same detector, as did Galileo when he made his first observations of the cosmos through his crude telescope. The technique is shared with that of Newton and the other visual pioneers who provided direction to our understanding of the Universe long before photography, photoelectric photometry, and CCD photometry were even conceived. The eye as a receptor has been a constant through millennia - visual observations made today can be connected to those made thousands of years ago.

I have been a visual observer for the past 53 years using the same detector, as did Galileo when he made his first observations of the cosmos through his crude telescope. The technique is shared with that of Newton and the other visual pioneers who provided direction to our understanding of the Universe long before photography, photoelectric photometry, and CCD photometry were even conceived. The eye as a receptor has been a constant through millennia - visual observations made today can be connected to those made thousands of years ago.

So, when I am at the telescope and see light from the stars in the field, I must think of the route those bits of energy must have gone through to give me the privilege of detecting their numbers and providing the information they provide in helping us understand the mechanics of the Universe.

This is a humbling experience considering the path these bits of energy made from the Big Bang to the eye of the observer.

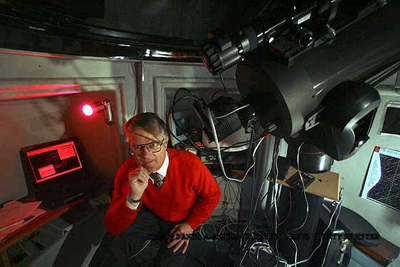

Michael Cook (CMJA)

I am star-stuff. The iron in my blood and the calcium in my bones was forged by stellar processes. As humans, we have in innate desire to know our origins. Biologists can link us back to the first humans and even back to the roots in the evolutionary tree of life. But we want to know more. It is through astronomy and astrophysics that we can discover our most fundamental origins using tools such as a telescope, CCD camera, photometry and spectroscopy - tools in my hands.

I am star-stuff. The iron in my blood and the calcium in my bones was forged by stellar processes. As humans, we have in innate desire to know our origins. Biologists can link us back to the first humans and even back to the roots in the evolutionary tree of life. But we want to know more. It is through astronomy and astrophysics that we can discover our most fundamental origins using tools such as a telescope, CCD camera, photometry and spectroscopy - tools in my hands.

Taking CCD images through Johnson-Cousins BVRI filters lets me obtain colour information of stars. This information can reveal many properties of a star and explain some of its behaviour. A spectrograph can obtain additional information about the stars, such as atomic and chemical abundances, and how that changes over time. The tools and techniques that are available can help me investigate and contribute to solving the mysteries of stellar processes and how stars provide the basic building blocks of planetary formation during their infancy and to life after they go supernova.

But observing not just any star will do! I want to see action in the data I collect. In this regard, observing intrinsic variables, such as Cataclysmic Variables (CVs) and Young Stellar Objects (YSOs), are my targets of choice. And what they have in common are accretion and/or obscuration disks that interact with the star, giving rise to significant variability. Studying accretion disks can also help to reveal similar physical processes involving planetary formation, stellar mergers, and black holes. And every star passes through the YSO stage, so studying these objects, in essence, enables us to study every star at some point in its evolution.

Observing these kinds of variability gives me a "piece of the action", and that motivates me to return to these objects night after night, limited only by the Sun and the horizon (and occasionally by the Moon), in an effort to contribute to our understanding not only of our place in the Cosmos, but in the words of Carl Sagan, as a "way for the Cosmos to know itself". Isn't that motivation enough?

Carl Knight (KCD)

The behaviour of stars late in their lives is my key interest. Highly evolved single or binary systems at all scales - ranging in peak emission from ultra-violet to the near infra-red. The numbers tell the stories of their dynamic nature in a code that we interpret as rotation, orbit, accretion, pulsation, radial velocity, temperature, proper motion, absorption, emission, ejection and detonation. The instruments at my disposal let me see the numbers from the visible to the near infra-red - to build a more complete picture in my head of what that star is up to tonight and on larger timescales to think about where that star is going - and in many cases, to wonder what it might be up to at all - semi-regular is perhaps better described as not-quite-completely-chaotic! This keeps me returning to the same stars again and again. It is what motivates me to spend nights outdoors whilst others sleep or to rise at 3am to see if I can get early photometry of a star recently returned from behind the sun.

The behaviour of stars late in their lives is my key interest. Highly evolved single or binary systems at all scales - ranging in peak emission from ultra-violet to the near infra-red. The numbers tell the stories of their dynamic nature in a code that we interpret as rotation, orbit, accretion, pulsation, radial velocity, temperature, proper motion, absorption, emission, ejection and detonation. The instruments at my disposal let me see the numbers from the visible to the near infra-red - to build a more complete picture in my head of what that star is up to tonight and on larger timescales to think about where that star is going - and in many cases, to wonder what it might be up to at all - semi-regular is perhaps better described as not-quite-completely-chaotic! This keeps me returning to the same stars again and again. It is what motivates me to spend nights outdoors whilst others sleep or to rise at 3am to see if I can get early photometry of a star recently returned from behind the sun.

Perhaps most importantly, I am in the company of excellent people who share the same sense of wonder and desire to understand - to whom such behaviour is anything but "odd".