April is the month of citizen science, astronomers, and volunteers!

AAVSO's volunteer observers are world wide, and are crucial to AAVSO's database and scientific research by professional astronomers!

We will introduce a different observer every few days throughout the month!

We reached out to our international observers to learn more about their personal astronomy stories, including how they got started with astronomy or the AAVSO, overcoming challenges to get to where they are in the scientific world, and how their AAVSO data contributed to particular research. We hope their stories inspire you to achieve your astronomy aspirations or get started!

If you are an AAVSO observer who has not submitted your story, and you would like to be highlighted, please submit it to aavso@aavso.org.

The initials next to each name is the unique AAVSO observer code (obscode) assigned to each person.

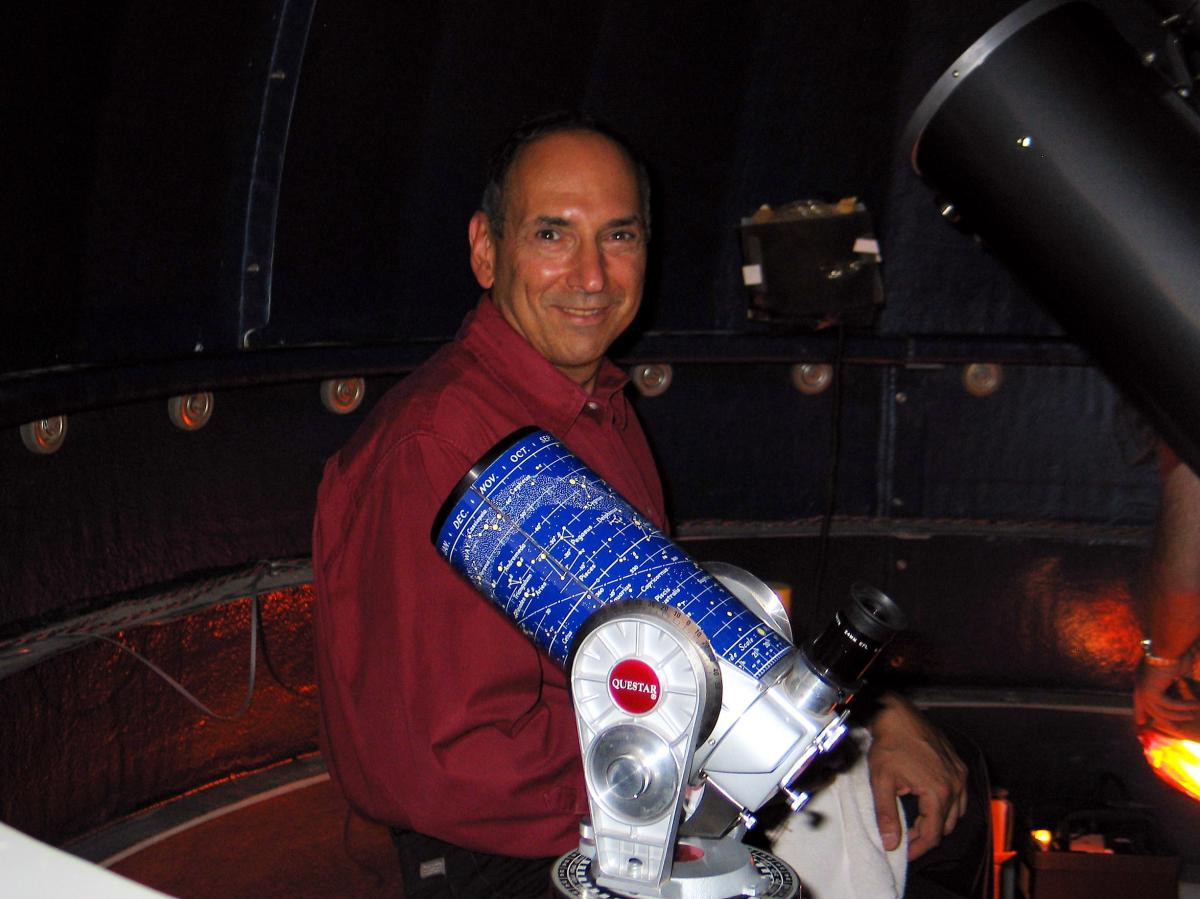

David Levy (LVY), United States

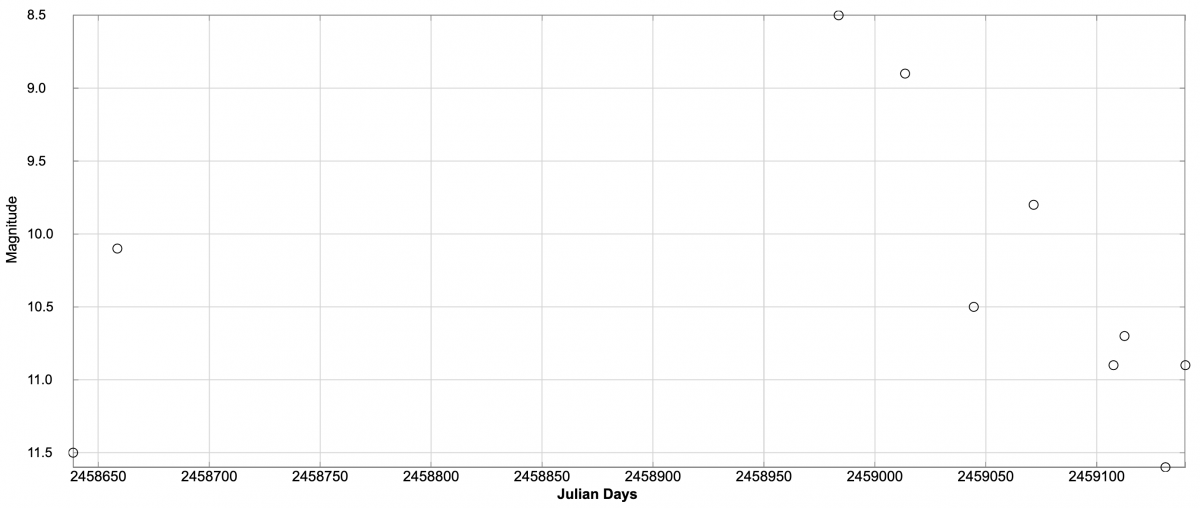

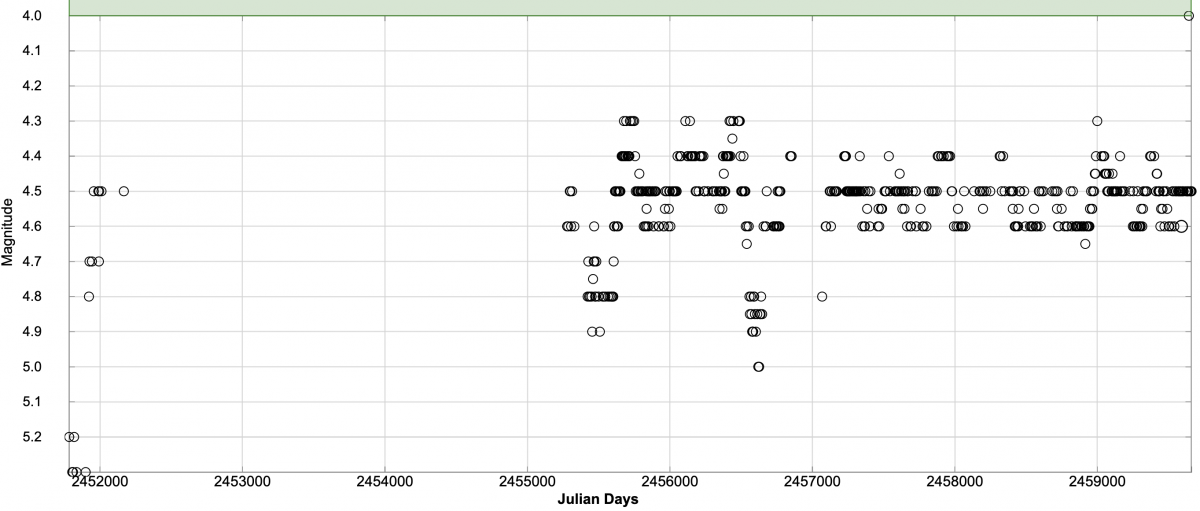

His visual observations of his most observed star, TV CRV:

Anyone can access and plot star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

His story:

|

I have been a member of the Montreal Centre of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada since May of 1964. One of the programs our director of observations had encouraged us to do was follow the behavior of certain bright variable stars, like g and X Herculis and RR Coronae Borealis. I did feel a bit guilty that I was observing and submitting reports to AAVSO without actually being a member, and so later I purchased an annual membership. (Depending on finances, my membership has bounced along from annual to sustaining and back.) Over the next few years, I gradually added more stars to my list. Then in January of 1973, I ordered several dozen charts of various stars. On August 30, 1975, I made an independent discovery of V1500 Cygni, the bright nova of that summer, and three years later, made a second independent discovery of V6668 Cygni, the nova from that year. In 1979, I relocated to Arizona to pursue my major astronomy project, my search for comets. For a long while, my numbers of variable star observations plummeted. |

While working on my biography of Clyde Tombaugh, the discoverer of Pluto, I learned that he had discovered what he thought was a nova in Corvus. I learned where the star was in Corvus, and from a search through the plate stacks at Harvard College Observatory, in 1989, I found nine later outbursts. Rather than a nova, it appears that Tombaugh had discovered a high galactic latitude cataclysmic variable star. I began a nightly program of checking the area. On March 22, I was able to check on the area using a telescope in Florida. Home the next night, March 23, 1990, 59 years to the day after Tombaugh first recorded the star on a photographic plate, I checked the area again with my own telescope and suddenly found the star, in outburst at just fainter than 12th magnitude. The star was eventually named TV Corvi but I have always referred to it as “Tombaugh’s star” in honor of the person who first saw it. It is my favorite variable star.

In the many years since, I began my life in Arizona, and I have concentrated more on comet hunting than on observing variable stars. However, the first of several observer guides I have written was on variable stars. And I still attempt nightly checks of Tombaugh’s star whenever its field is above the horizon. I also follow Alpha Orionis and T Coronae Borealis. I have very much enjoyed my long and happy membership in the AAVSO.

With all best wishes,

David Levy

Keep scrolling to see more observer stories!

Mike Poxon (POX), United Kingdom

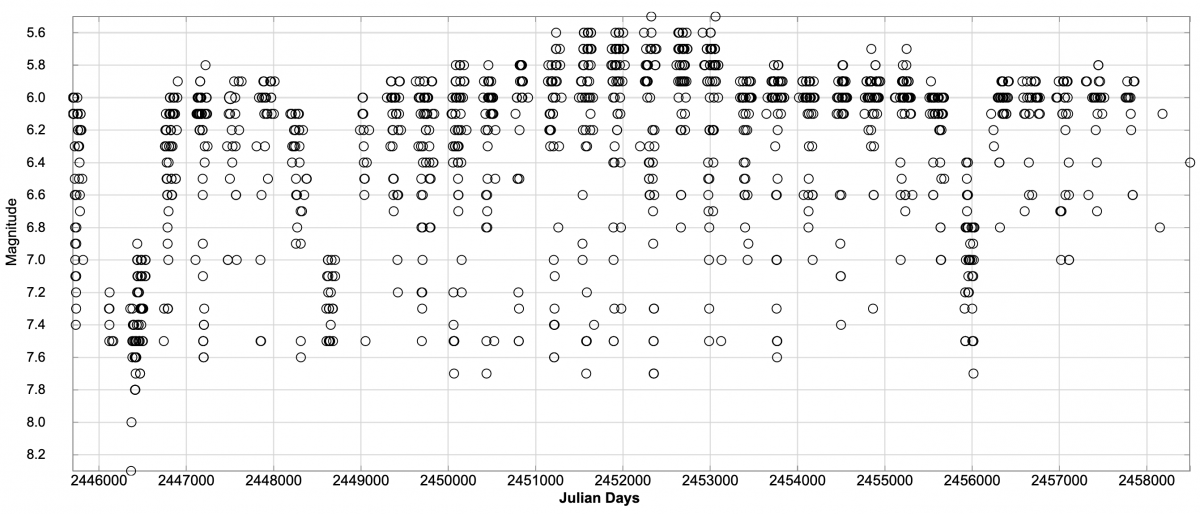

His visual observations of his most observed star, Z CAM:

Anyone can access and plot star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

His story:

|

I was born in a British seaside town, an only child, to very poor parents who had not had much education, but who wanted me to have one! They bought a set of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedias and I devoured every one of the ten volumes, with the result that at age five, I could read perfectly and had started to learn French as well! However, it was the lovely pictures of the night sky in those thick volumes that stirred my imagination. No flashy photographs, just simple pictures; I loved the stars and the patterns they made and soon learned their names and stories. However, the event that really hit home was when I was about six or seven, and my parents were house-sitting for a grown-up cousin who was giving birth in the hospital. On the way home in the evening, we were waiting for the bus, when I had what I later learned was called a “religious experience.” I remember just looking up at the Plough (“big dipper” in the USA) when time stopped and I was ‘taken up’ into the whole universe and the universe was taken into me. After such an intense and unforgettable experience, the stars became, in essence, the brothers and sisters I never had. From that time, all I wanted to do was learn as much about the sky as possible. |

Therefore, my interest in astronomy was, and still is, inclined at heart towards the ‘artistic’ or ‘spiritual’—even though I write astronomical software, run an international group studying star formation, and work with astronomical surveys and dedicated satellite missions! I see no conflict in any of this. I still love to show people the constellations, and tell them the names of the stars and even what they mean (my degree is in linguistics, and I like to invent languages as well).

Keep scrolling to see more observer stories!

Joe Ulowetz (UJHA), United States

His CV observations of his most observed star, AM CVN:

Anyone can access and plot star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

From Joe: "My top ten list: Unexpected events that happened while observing"

|

Number 10. When I was in graduate school at Yerkes, I used the telescopes there to stargaze at times (they actually weren’t that good for doing that), but I wasn’t trained on using the big 40” refractor. One nice evening it was clear, and the refractor wasn’t in use, so I asked one of the maintenance people if he could point the telescope at Saturn. While he was doing that, I asked what it would take for me to be trained to operate the telescope. He said he was showing me what to do at that moment, and that this counted as training! Great. Some time later, it was again clear and no one was on the refractor at the moment, so I opened it up and looked at some targets. At one point, I wanted to do a pier flip to observe the other hemisphere, and when the telescope was partly turned around, with the eyepiece end way up in the air, the power relays shut off and I couldn’t move the scope with the controls from the observing desk. I confirmed that I could close the dome, and then woke up one of the astronomy professors for my chewing out. I remember him saying, “That is why we don’t stargaze with the 40" refractor,” and that someone would figure it out in the morning since the dome slit was closed and the scope was safe. The next day, I found out that the hand paddle control at the telescope eyepiece had been lying against the emergency stop button (way up in the air) when I did the pier flip, and that is why it stopped. I never used that telescope again by myself, but now I wish I had just learned from my mistake and continued to use it when it was available. |

Number 9. My first summer as a grad student at Yerkes, I was alone in the 41” reflector dome setting up to do some photography. I noticed a light coming up the stairs on the side of the dome; I assumed it was someone with one of those small LED flashlights was walking up the stairs. I suddenly realized I could see the wall through where I thought the person was! I grew up in the Pacific Northwest. where we don’t have lightning bugs. My introduction to lightning bugs gave me quite a shock.

Number 8. About two winters ago, I went out to use my telescope on a beautifully clear and cold night after a few days of above-freezing temperatures had melted the snow. I found that the melt water had formed a puddle in front of my observatory door and then frozen, and the bottom of the door was blocked from opening by the ice. I tried to chip it away with a shovel, but ice is hard. So I went to the hardware store and bought 10 pounds of sidewalk salt, and dumped the whole bag on the ice in front of the door. The next evening it had dissolved enough ice that I could open the door again, so I only lost one night to ice.

Number 7. About 10 years ago, a mountain lion was found in Chicago and unfortunately had to be killed. They said it probably followed the railroad tracks to get so far into the city. I realized it might have passed my observatory which is next to the train tracks, and that I might have been out when that happened. I never thought I’d have to worry about mountain lions when using my observatory since I was in suburban Chicago!

Number 6. In high school, many years ago, I went to a star party with my local club and took my friend and my telescope. But I had forgotten a piece of the telescope, so I left my friend with my telescope in the city park to drive home and get the missing piece, but the car (the only one my family had) started acting up and I barely made it home, leaving my friend and telescope stranded on the far side of the city. (This was all in the days long before cell phones, of course.) Fortunately, my friend’s mother gave me a ride and we worked out a return trip with other club members there.

Number 5: In 7th grade with my first telescope, I got up at 2 a.m. to view that part of the sky for the first time with my telescope. I forgot that we had automatic lawn sprinklers and they went off suddenly in the quiet night. I didn't get too wet, but it certainly gave me a scare.

Number 4: Looking for Comet Kohoutek in 1974 at 4 a.m. by the side of a county road near my home, and a State Policeman stops. I was only 17 at the time and didn’t know if I was going to get in trouble for “curfew.” It turned out all he wanted was a place to eat his “lunch;” he was very nice about it and asked me if he would be bothering me.

Number 3: Camping in the Cascade Mountains in high school. The stars that night were so bright that I could not pick out constellations, just star clouds of the Milky Way. What a view! Later that night in my tent, something started poking my foot through the tent wall. I pushed back, but then it started poking me again. I kicked as hard as I could and it stopped. Never found out what it was; probably a raccoon, but it could have been a bear.

Number 2: Observing after our club meeting about 10+ years ago. We always met in a nature preserve, and there was a gate that would normally be locked, but on meeting nights the gate stayed open until we were done. But that night I stayed late with a couple of other club members, stargazing from the parking lot. I decided to go home while two others remained observing, but when I tried to leave the nature preserve I found I was locked in! So I wandered around the grounds of the nature preserve until I found a house with lights on. I went to ask them to let me out, but they were the cleaning crew and none of them spoke English. However, they did call someone and put me on the phone to explain I needed the gate unlocked. But I never had the chance to explain that two others were still here and would need to get out also. So whoever you were, I’m sorry you probably had to go through the same adventure as me.

Number 1 story: a couple years ago, in August, after setting up my observatory in my backyard, I headed back to my house and saw a skunk between me and it. No problem; I was far from it so I yelled at it to get its attention. It ran from me towards my house, not around it, towards the laundry room that was at ground level and where it would be able to spray through the screen window if it was threatened. I froze, hoping that no one was in that room at that moment. Fortunately, after a few seconds it turned around and ran the other way along the back of my house, but then it hid in a small bush right next to my back door, which was closed but was the only unlocked door. Locked out of my house by a skunk! I didn’t want to try to sneak past it. Fortunately, I got someone to open the front door for me–and I immediately closed the laundry room window, just in case.

Keep scrolling to see more observer stories!

Albert Lamperti (LALB), United States

His visual observations of his most observed star, SS CYG:

Anyone can access and plot star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

His story:

|

Back in 1984, our older son bought himself a small telescope and we viewed Jupiter & its moon, and the rings of Saturn from our front yard. That rekindled my interest in astronomy, as I too had a small telescope when I was young and living in the Bronx. At the time, I knew very little about the sky or the hobby. My wife saw an ad in the local paper for a star party given by the local astronomy club. A year later, I bought a telescope and have sold and bought several since then.

I was introduced to the AAVSO in 2015, when one of the requirements of the Binocular Variable Star Program was to upload my observations into an AAVSO database. More recently, one of the requirements of the Nova Program is to do the same. I currently have a modest 138 observations in the AAVSO database. Hopefully, next May, there will be an article published that we are currently writing for Sky & Telescope magazine about Variable Galaxies. Readers are encouraged to upload their data as well.

|

I also enjoy the Astronomical League’s (A.L.) lists of celestial objects, finding them, and being rewarded with a certificate from the organization for finishing that list. After 40+ lists, I am still chugging along. I retired early as a professor of Anatomy & Cell Biology from Temple University so I could have more time to devote to astronomy and to travel. I am still involved with the A.L. and am one of four members of the National Observing Program team that helps oversee the A.L. Observing Programs. As Program Coordinator for the Active Galactic Nuclei Observing Program of the A.L., I encourage folks to observe AGNs, and also note the magnitudes of the variable galaxies (a list is provided) and upload the information into the AAVSO database.

Having been in the science field as part of my employment at universities, I am fully aware of the time it takes to get even a single data point on a graph. So any contribution, however small, benefits those researchers analyzing the thousands of data points looking for trends and variations. Every small bit helps!

--Al

Keep scrolling to see more observer stories!

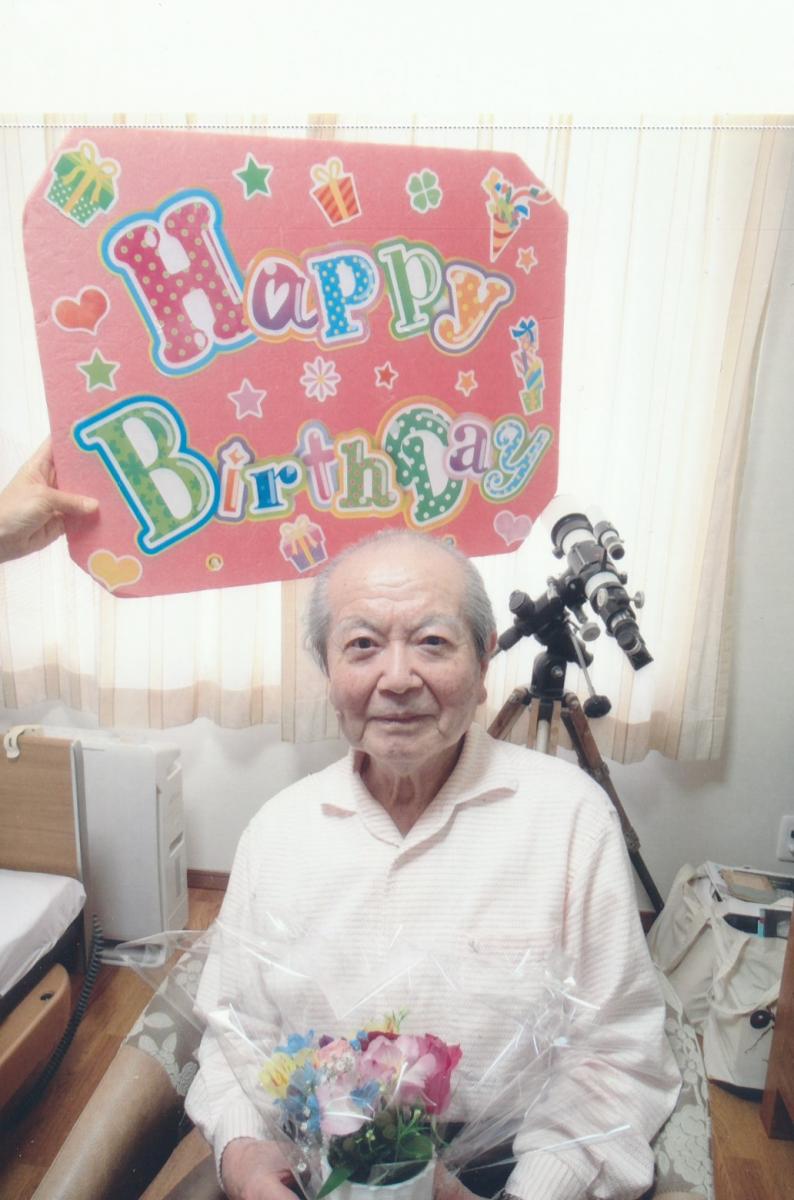

Seiichi Sakuma (SSU), Japan

His visual observations of his most observed star, U MON:

Anyone can access and plot star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

His story:

|

An ancestor of mine was a Samurai in Kyushu. I was born in Tokyo in 1929. World War 2 ended in 1945—at that time I was the youngest naval cadet at age 16. Japan was defeated by an atomic bomb, radio locater, and so on. To rehabilitate the postwar Japan, it was regarded important to promote science and technology; I majored in chemical engineering and graduated from Yokohama Technical Collage and Tokyo Institute of Technology (TIT). Astronomy is my hobby. I entered the Japan Astronomical Study Association (JASA), which was established in 1945 by Dr. S. Kanda, who was a retired astronomer of Tokyo Astronomical Observatory, and an AAVSO observer. I contacted AAVSO in 1950, as a chairman of the Var. Star Section of JASA. Popular Astronomy (just before discontinuance) reported the situation of Japan’s Var. Star Observation by me. In 1955, I learned of the book by Leon Campbell, Studies of Long Period Variables” and purchased it through Mrs. Mayall. Since 1955, my name, Seiichi Sakuma, has been registered in the table of Non-Member, Observer, and Exchangers. |

In 1974, Dr. S. Kanda died, and JASA had no funding. I was thinking that reported variable star estimates would be impossible to print and publish in the near future. It was best for Japanese obs. data to join the AAVSO Int’l database (AID). At first, in order to carry this out, I applied to be a member of AAVSO, and I started to report my observations to AAVSO in Jan. 1984. My membership application was accepted at the Spring Meeting in Ames, Iowa, May 26,1984.

I was studying about Miss Jenkins, getting the data of her Mount Holyoke Collage era from Dr. Hoffleit. I wrote a paper titled “Louis F. Jenkins, Astronomer and Missionary in Japan.“ This was read by E.O. Waagen at the 74th Annual Meeting (South Hadley, Nov.1985). This was my first paper in the JAAVSO.

It is my great pleasure to recall attending the 75th Anniversary Meeting (Aug. 6-10, 1986 in Cambridge, Mass.). I made several calls to the U.S. from Japan prior, but was visiting for the first time. The Meeting and Dedication of the Clinton B. Ford Data and Research Center were in preparation with a friendly atmosphere…”Come and join in this once-in-a-lifetime occasion”… for instance, dormitory rooms at Harvard University had been reserved. I had a chance to announce “AAVSO and the Japanese observers” and “Present Status of Variable Star Observation in Japan.” At the Poem and Song Contest, I played by SONY’s tape recorder to get Tanimura Sinji (Japan’s most famous singer) to sing “Subaru: Pleiades.” I got a golf cap as prize. At social hour, Mrs. Katherine Hazen told me “I know Prof. Shun-ichi Uchida.” Prof. Uchida was the pioneer of chemical engineering in Japan and I made my thesis instructed by him at TIT. Later, I received a letter of condolence for Emperor Hirohito’s death. She and her husband, Prof. Hazen were invited to the Imperial Palace as the president of the mission for industrial education about 5 years after the end of World War 2.

To my regret, my paper “The Apsidal Motion of the Eclipsing Variable V356 Sgr” was rejected for publication in JAAVSO. The reason was because Gaposchkin’s data, which I used in my paper, were taken over a period of nearly 50 years and records of exact dates could not be found.

After my first Meeting, I always accompanied my wife Nobuko to AAVSO Meetings. Mattei-san was fond of gardening, same as Nobuko. At 87th Spring Meeting (Border Colorado, June 1998), Mattei-san and Nobuko found forget-me-nots among the snow field of Mt. Evans on the trip. Exchange of photographs of flowers was continued till 2003.

June 20-29, 1987, I attended to “The Contribution of Amateur Astronomers to Astronomy“ and planned to go to Hungary to meet Dr. Attila Mizser. I met Dr. Mattei again and asked for an “image intensifier” as a gift to Konkoly Observatory from AAVSO, which was given.

May 3, 1988, I received an int’l telegram from Mattei-san, “I am very happy to inform you that your observation of IR Gem on 2448189.1 at 13.2 mag. was the 6 millionth observation in AAVSO Database. Thank you very much for helping AAVSO reach this important milestone.”

In 1988, roughly 100,000 observations were reported to JASA and NHK (Nippon Henkosei Kenkyukai), Research Group for Variable Stars in Japan). The number of observations was increasing rapidly because of activity of some cataclysmic star observers. Dr. M. Huruhata, retired president of Tokyo Astro. Observatory and former AAVSO observer, eagerly advised to report the results in English (not Japanese). Computerizing the archive was easy and not too expensive. Under these circumstance, VSOLJ (Variable Star Observer Leabue in Japan) was established in the National Science Museum In 1987. VSOLJ’s aims were, 1: publish the Bulletin, 2: carry out the MIRA (Million data Input, Reduction, and Archiving) project. The input system was independent of AAVSO’s.

I and Nobuko enjoyed very much the AAVSO Meeting in Europe; twice: July 1990 in Belgium, and May 1997 in Switzerland for the 86th Spring Meeting.

Feb. 20, 1993, at the Dr. Clinton B. Ford Memory Meeting, I sent a message and flower via AMEX service because almost of all of the advanced Japanese observers received Dr. Clinton Ford’s service when they used the Preliminary Charts.

I started to report to AAVSO using MEAD DS16 (40cm reflector) in order to get “inner sanctum observation;” Apr. 1994, MEAD LX200-25cm SC with CCD ST-6 was installed with 30sec exposed image (no filter) reach at 17mag.

I had many acquaintances through AAVSO, and I visited their homes, most times with Nobuko: 1987, Dr. Mizser in Hungary; 1990, Dr. Kucinsca in Lithuania; 1993, Mr. Albrecht in Hawaii; 1995,Dr. Bateson in N.Z.; 1996, Rev. Evans in Australia.

My presentation, “Japan’s First Variable Star Observer, Dr. Naozo Ichinohe,” that I gave in 2002 at the Spring Meeting was published in JAAVSO Vol. 31-1 (2002).

At the Oct. 2004 memorial symposium to honor Dr.Mattei, I talked of “Dr. Mattei in Japan (JAAVSO Vol. 33-2, 2005).

At the 100th memorial meeting in Oct. 2011, I presented, “Star Watching Promoted by the Ministry of the Environment Japan (JAAVSO Vol. 40-1, 2012)

In 2015, I donated my astronomical instrument to an observation spot, which is operated by my junior of high school. It is situated at the mountain side of Yamanashi Prefecture.

Three years ago, Nobuko died. 2 years ago, I transferred to an old-age home, and brought with me my Takahashi 65mm refractor and binoculars. Sometimes I observe variable stars by use of them, and report to AAVSO.

Keep scrolling to see more observer stories!

Angelito Sing (SANG), Philippines

His visual observations of his most observed star, BET LYR:

Anyone can access and plot star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

His story:

Ever since I was young, I was really interested in astronomy. My interest in variable stars started with a book, Peterson's Field Guide. In that book is an observing chart for Mira, which I used to observe. After a few months, Sky & Telescope magazine published an article showing the light curve of Mira. I plotted my own observations and discovered that it agreed with the light curve in the magazine…I was amazed that I could really observe the variability of a star, so I joined the AAVSO–I think around 2006. Since then, I have submitted more than 9.4K observations!

Keep scrolling to see more observer stories!

Veikko Mäkelä (MVO), Finland

His visual observations of his most observed star, RHO CAS:

Anyone can access and plot star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

His story:

|

I am an amateur astronomer from Helsinki, Finland. I am working as an IT project manager at the University of Helsinki, but amateur astronomy is a big part of my free time. My interest in astronomy began somewhere in the early 1970’s. I could say I belong to the space generation. I was 7 years old when Neil Armstrong took his small step for man and giant leap for mankind. So I guess Apollo missions were one of things that inspired me to get involved in astronomy. Observational astronomy has always been my favorite. I have observed all kinds of targets: the Sun, moon, planets, comets, and deep sky and atmospheric optics. I started variable star observing in the mid-1970s. For that, I have to thank my mentor, Mr. Aarre Kellomäki, who was the ‘Grand Old Man’ of variable star observing in Finland for many decades. First, we collected Scandinavian observations together. When the cooperation ended in the 1990s, it took me a while to start sending my data to AAVSO. Recently, I was notified that I reported the first observation to the database 20 years ago. Of course, I have known AAVSO from the 1970s, when I started my variable star hobby, and I have been involved since the beginning of this millennium. First as an observer, later as a member too. |

My astronomy hobby led me to the university to study astronomy. I never became a scientist—there are several reasons for that—computers and ITC took my path in another direction, but not far, because I am still working at my alma mater/home university in support and administration. BUT, my hobby of astronomy still remains strong. When I had been working for several years in the IT department, I got my MSc degree to conclude what was unfinished. My Master thesis was about time series analysis of BD Ceti, a RS CVn star with star spot activity.

I was a much more active observer when I was younger. With my friend, we made a thousand or more visual estimations a year. Nowadays, I record maybe two hundred observations or so. I have always been a binocular or unaided eye observer. Semi-regulars and low-amplitude irregulars could be rather boring for those who find “quick wins.” As stars become familiar and you learn their behaviors, though, sometimes you get some surprises too.

Two of my observational highlights:

From 2009 to 2011, when Epsilon Aurigae had its minimum, I followed the star, among several others. The center of the minimum was in the summer of 2010, when the star was quite near the Sun, maybe about 20 degrees or so. In Finland, the nights are very light in the summer, but the star is circumpolar. So, I attained some observations, even when it was very hard. At that time, few observers in the world could follow the star during a period of some weeks, and I was one of them. I even got named into a circular.

Another nice highlight was in the winter of 2019/20, when Betelgeuse went into deep minimum: I could say, “for a long time, observing variable stars with my unaided eye has not been as interesting, as it is now.”

Keep scrolling to see more observer stories!

Rod Stubbings (SRX), Australia

Rod started with a simple telescope and a book about how to find stars without a telescope!

His visual observations of his most observed star, OY Car:

Anyone can access star observations using AAVSO's Light Curve Generator

His story:

|

G’day! I’m Rod Stubbings and for the past 27 years I have been dedicating my time, resources, and sleep to the field of variable stars. In southern Victoria at the foothills of the Strzelecki Ranges, my humble set up, Tetoora Road Observatory (D03-35), is a registered Australian observatory for optical research on variable stars. My interest in astronomy started in 1986 when I came across an advertisement in Reader's Digest for a 65mm Tasco telescope that would allow me to view Saturn’s rings and Jupiter’s belts. I caved to consumerism and skilled marketing and bought said scope; however, I quickly realised that I had no clue where to look and where to point the darn thing. I figured I would need to start at the basics, so I bought the book Astronomy Without a Telescope, which provided in layman’s terms how to navigate the night sky. After a few years of spending countless hours learning the night sky from charts and getting my bearings in the astronomical world, I was introduced to the field of variable stars at the Latrobe Valley Astronomical Society by a fellow colleague. Since I was already spending a considerable amount of time observing the night sky, it seemed like a great opportunity to use my time and resources to contribute to science. And so, equipped with a beginner’s book on The Observations of Variable Stars from the Royal Astronomical Society of New Zealand (RASNZ), I taught myself how to observe, record, monitor, and measure variable stars. |

I made my first observation on the Mira star R Cen in May 1993. Within the first month, I recorded 10 observations and became a member of the RASNZ. My attention eventually shifted to cataclysmic variables, particularly the U Gem type, as I enjoyed the unpredictability and ever-changing nature of this category of stars. When I first started observing, it looked very different to how we operate these days. All contact was made by post or phone without the convenience of emails. Professional astronomers needed close monitoring from amateur astronomers so they could undertake satellite observations when these U Gem stars went into an outburst. This program set up by professional astronomers was often referred to as "targets of opportunity" (TOO). When an outburst was detected, it needed to be phoned in to the RASNZ director, Dr Frank Bateson, and he would then alert the relevant professionals. I remember the first time I called in a TOO to Frank, it was the SU UMa eclipsing type dwarf nova OY Carinae, which I detected an outburst of at 2:00 a.m. I questioned whether I should ring at this time of night or whether he would even be awake. In the end, I decided to make the call, which was well received and enabled the satellite observations to take place. Over the years, the way we observe, monitor, record, and alert relevant authorities has evolved with technological advances, and continues to change the way we view the night sky.

As the internet picked up, I came across the Variable Star Network (VSNET), a global professional-amateur network of researchers in variable star and related object alert mailing lists, which also reported outbursts of stars. While reading the VSNET alerts, I realised there were numerous observations and outbursts that I had submitted to the RASNZ that were not reported on the alert lists. In early 1997, I decided to send out every outburst detection to VSNET, which soon turned out to be quite a few and more of a second job rather than just a hobby. I chose to concentrate on the cataclysmic variables which were not as commonly studied, and searched through all the catalogues and added the unstudied and fainter dwarf novae to my list. This meant that I was monitoring a lot of stars that were having outbursts at magnitude 15.0 to 15.6. With constant monitoring, I was able to record their maximum brightnesses, frequency, duration, and follow the rise and fall of outbursts; all this information was previously unknown. At this point, I was now averaging over 1,400 observations a month and detecting between 30 to 50 dwarf novae outbursts each month. My involvement with the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) began in July 1997. I received an email from the Director, Dr. Janet Mattei (1943-2004): “If you would be interested in sending your observations directly to the AAVSO, in addition to the other networks to which you send them, we would very much like to include your observations in the AAVSO News Flashes.” This was a further encouragement to continue observing and contributing to the field of science.

Over the years I have been honoured to receive many requests from astronomers around the world for notifications on specific stars that went into outburst, to assist their research programs. It is surreal to think that my observations have directly triggered satellite observations with the EUVE and XTE satellites, European X-ray satellite BeppoSAX, Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer (RXTE) satellite, Hubble Space Telescope, Chandra satellite, Fuse satellite, XMM-Newton, Swift satellite, Australian Telescope Compact Array, the MeerKAT Telescope in South Africa, and The Southern African Large Telescope (SALT). For me, it’s the collaborations that make variable star observing so rewarding. It’s the networking and meeting other professionals, receiving requests, discussing observing programs, and seeing your work triggering satellite observations and publications, that keeps me motivated.

|

|

In 2015, I decided to upgrade to a larger telescope to further enhance my visual observing. I acquired a 22” f/3.8 Dobsonian telescope and custom-designed to fit permanently into a 3.8-meter traditional domed observatory. I decided on these specifications in order to study my growing list of dwarf novae stars at fainter levels, and in a lot of cases, at their minimum. Although the telescope is fitted with ServoCat, Nexus with built in GPS, and WiF, this system is not used to find variable star fields. The locations and magnitudes of countless guide stars, along with hundreds of variable stars and their associated reference stars, are all found by memory. |

Since my upgrade, I am now getting to know these stars and their behaviour at these levels, and obtaining more positive estimates.

Although I have had the opportunity to switch to computerised observations, I have decided to stick with traditional forms of observing. I still see the need for visual observations and personally find my methods to be more rewarding, and observing under the night sky in real time is rather cathartic. After 27 years, one may think that novelty may wear off with the late nights, sleep deprivation, and reheating dinners, however, I am just as motivated as always. For me, astronomy to me has been more of a way of life than a hobby.