An ambitious project to digitize much of Harvard’s collection of more than half a million astronomical photographic glass plates has reached a significant milestone. | By Tim Lyster

As the largest archive of its kind in the world, Harvard College Observatory’s Astronomical Photographic Glass Plate collection comprises more than 550,000 glass plate negatives and spectral images, exposed in both the northern and southern hemispheres between 1885 and 1993.

While the repository contains a trove of astrometric and photometric information of the entire sky, accessing the data previously required the careful handling of fragile glass plates.

The Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard (DASCH) project changed that by deploying a high-resolution scanner to capture each plate as a digital image file. Launched on February 1, 2005, DASCH logged its final scan on March 28, 2024, having converted 435,763 plates into their digital equivalents.

To provide access for both researchers and the general public, the DASCH team launched StarGlass, an online portal that allows researchers and the lay public alike to explore the plate stacks collection.

Through StarGlass, users can search for objects by name and coordinates, or display all images captured on specific dates. There’s also the option to browse plates associated with particular astronomers, including members of the Harvard Computers such as Annie Jump Cannon, Williamina Fleming, and Henrietta Swan Leavitt.

Time-Domain Astronomy

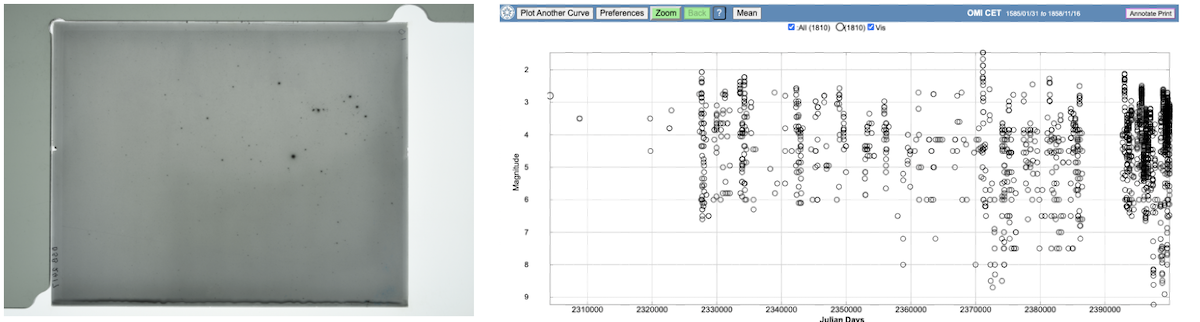

DASCH will facilitate “time-domain astronomy” science—the study of how astronomical objects change with time—by supporting the production of lightcurves with 0.1 magnitude uncertainties over 100-year timescales, in the same way the AAVSO’s Light Curve Generator (LCG2) can draw upon the organization’s vast archives to plot both current and historic observations. Indeed, LCG2’s range exceeds DASCH, as it includes large numbers of transcribed records, some dating as far back as the sixteenth century.

These two data repositories are complimentary, and offer curious readers the opportunity to compare data in interesting ways. A budding researcher might identify gaps in one database and then see if the other one provides coverage for the afflicted area, or “validate” on dataset versus the other.

![]() Like this content? Want to see more? Support AAVSO’s day-to-day operational needs with a tax-deductible contribution.

Like this content? Want to see more? Support AAVSO’s day-to-day operational needs with a tax-deductible contribution.

For example, an “Days All” plot of the eruptive variable SS Cyg on LCG2 reveals that AAVSO observers haven’t missed an eruption since the 1890s—an unbroken streak lasting more than 130 years, made up of more than 340,000 individual observations! Over at StarGlass, a similar search identifies more than ten thousand plates with the cataclysmic variable.

Then there may be objects lurking within the data that display as-yet undetected variability—or just plain weird behavior—over very long timescales. These kinds of databases are in effect time machines, allowing the armchair traveler the ability to “observe” stars as they were in the past.

The Astronomical Photographic Glass Plate collection is just one example, albeit large, of these kinds of repositories, some carefully preserved and indexed, others stashed away in non-optimal conditions, largely forgotten. The Wide-Field Plate Database holds “descriptive information for . . . astronomical wide-field (>1°) photographic observations stored in numerous archives all over the world. The total number of these observations, obtained since the end of the 19th century with more than 200 telescopes, is about 2,550,000 from 509 archives.”

What strange and wonderful data lies buried in these enormous astronomical libraries? What discoveries will be unearthed when digitization and data processing combine to provide global access? Will the next discoverer of a new category of variable star be a professional researcher—or an inquisitive citizen scientist with a computer, Internet access, and an eye for detail? ![]()