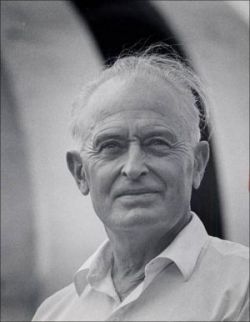

"The world's greatest non-professional astronomer."

"The world's greatest non-professional astronomer."

That is what Harlow Shapley called Leslie Peltier. If that is true, then why don't more people know about Peltier? I think the simple truth is he was a very private, soft-spoken man, who never sought the limelight and would have been embarrassed by all the attention he gets nowadays.

I've tried several times to write about Leslie Peltier, but every time before, I have begun thumbing through his classic book, Starlight Nights, for references and quotes and ended up reading the whole thing from cover to cover again instead of writing the piece that was my original intention. I'll never get tired of reading it. There are a lot of books that tell you how to observe the heavens and what you will find when you do, but this book always reminds me of why I love to be out under the stars at the eyepiece of a telescope, soaking in the sounds and smells of nature and admiring the majesty of the universe with my own eyes.

Born in January 1900, on a farm outside of Delphos, Ohio, Leslie grew up in a less complicated time, among the forests and farm fields of the area he lived his entire life. If he was famous for anything, it was his unwillingness to leave his home. He had everything he needed right there in Delphos- his family, his home, his gardens, and his observatories. Why would he want to leave any of that? So it was, that later in his life people made the pilgrimage to come visit him. Leslie was not likely to be making a public appearance anywhere near you. You had to go to the mountain.

As a boy Leslie was fascinated by the natural world around him. He read books from his family's home library and learned abut the flora and fauna that appeared on and around his home in nature guides, such as Wood's Natural History and Gray's Botany. He thoroughly enjoyed identifying each new butterfly, bird and flower. In 1977 he published The Place On Jennings Creek, a book relating the past 25 years of gardens and critters that shared the natural setting of his home with Leslie and his wife, Dorothy.

It's kind of surprising that it took Leslie until he was in high school to realize that his natural world extended upwards, over the tree tops, past the clouds and out into the Universe into the night sky. He recalls in Starlight Nights the moment it dawned in him that he could name all the butterflies on his farm but didn't know the names of any of the stars in the heavens. One evening in May-

"Something- perhaps it was a meteor- caused me to look up for a moment. Then, literally out of that clear sky, I suddenly asked myself: "Why do I not know a single one of those stars?"

Thus began an epic journey of discovery and observation that lasted the rest of his life. Peltier learned the stars on his own using only his eyes for the first year. He always felt this was the best way to learn the sky, as opposed to having someone teach the constellations or telescopic showpieces without investing the time and effort to become familiar with each one and its place in the heavens.

"Each star had cost an effort. For each there had been planning, watching and anticipation. Each one recalled to me a place, a time, a season. Each one now has a personality. The stars, in short, had become my stars."

His first telescope was purchased with earnings from picking strawberries. He had to pick 900 quarts at two cents a piece one summer to save up the $18.00 for his mail order 2" spyglass telescope. He made his own alt-azimuth mount for the telescope out of a left over fence post, an old grind stone and discarded two by fours. This telescope served him well as he learned the sky and how to use a telescope to view the heavens.

His fatal attraction to variable stars and the AAVSO began when he wrote a letter to AAVSO founder, William Tyler Olcott asking how he could contribute to science with his small telescope. Olcott wrote back explaining that observing variable stars was an exciting and scientifically useful way to spend ones time under the stars, and from the time Leslie was eighteen until his death in 1980 he never missed sending in a monthly report of variable star observations to AAVSO headquarters in Cambridge, MA. His description of how variable star observing changed his life forever is something I have quoted often to many people.

"Life was never quite the same for me after that winter walk to town. The charts that I brought home with me were potent and ensnaring and I feel it my duty to warn any others who may show signs of star susceptibility that they approach the observing of variable stars with the utmost caution. It is easy to become and addict and, as usual, the longer the indulgence is continued the more difficult it becomes to go back to a normal life."

In 1919, Peltier was given the first of several telescopes that would be loaned, or given to him outright, based on his exceptional observing skills and perseverance. The AAVSO loaned him a 4-inch refractor with which to make variable star observations, and he immediately put it to good use by observing even fainter variable stars. Two years later, after enduring hundreds of nights in the dew and cold his father suggested it was time they build a proper observatory for Leslie. This observatory soon housed an even larger telescope, the 'Comet-Catcher.'

In 1925, he discovered his first comet, using the Comet-Catcher, a 6-inch refractor on loan from Henry Norris Russell of Princeton University. He would go on to discover 11 more comets in his lifetime, the last one in 1954. He also discovered four naked eye novae and made a habit of checking up on some old novae that still varied and occasionally had recurrent outbursts.

In 1959, life took a very unexpected turn when Miami of Ohio University offered to give Leslie their 12-inch Clark refractor, complete with observatory, dome and transit room! The entire observatory was cut into sections and delivered 125 miles to the Peltier home, where it was re-assembled and served Leslie as he strove to observe the faint minima of many of the variables he followed for decades. With this telescope he could follow stars down to 15th or 16th magnitude, far fainter than his other telescopes would allow. In total, Leslie Peltier submitted over 132,000 variable star observations to the AAVSO, making him one of the all-time leading observers in history.

Peltier's life was a long, steady, calm procession of days and nights lived to the fullest and enjoyed for their blessings, punctuated by events like the appearance of a new comet or nova, or unexpected recognitions for doing what Leslie would have done even if no one noticed.

Overcoming his lack of formal education, Leslie dropped out of school after the 10th grade to work on his father's farm, he received an honorary doctorate from Bowling Green State University in 1947. In 1965, a mountain in California, home of the AAVSO's Ford Observatory, was named Mt. Peltier in his honor. In 1975, he received an honorary high school diploma from his home town's Delphos Jefferson High School.

In his obituary, written by friend and fellow AAVSOer, Carolyn Hurless, she says, "Leslie was able to accomplish all he did because he was a private person. He lived exactly as he wanted to. He did nothing he didn't wish to do and was able to say "no" very easily. He was very uncomfortable with those who sought him out because he was famous, but to those fellow variable star observers who visited, he was a warm and welcoming individual."

Shortly after his death in 1980, the Astronomical League established The Leslie C. Peltier Award "to be presented to an amateur astronomer who contributes to astronomy observations of lasting significance," and that is where our histories finally intersect. In July 2012, I became the 30th recipient of the Leslie Peltier Award at the Astronomical League Convention in Chicago, Illinois.

Finding myself uncharacteristically speechless and unprepared, this is what I wish I would have said when asked to say a few words.

"I've known about Leslie Peltier, the great amateur astronomer and variable star observer, for years. I've heard the reverence in people's voices when he is mentioned in conversation. I've read Starlight Nights more than any other book I can think of. And when I do, I'm always struck by the similarities in our experiences.

I too learned the sky and the names of all the stars and constellations on my own, through books and star charts borrowed from the library. I earned the money to buy my first telescope by getting up early in the morning and delivering papers door to door for far longer than I ever dreamed I could endure. His story about seeing something in the sky he couldn't explain during the UFO crazed 1950's, and the fact that it turned out to be geese flying in formation, is exactly like the story I have told my friends and will share with my grandchildren one day, about a winter night in 1980. I too, have received a telescope on loan from the AAVSO, as well as a CCD with which to observe variable stars. Even the opening paragraphs of Starlight Nights, where he describes walking down the path towards the two stark-white structures as night falls reminds me of my walk to my observatories each clear night.

But when he writes about his love of variable stars, and how he gets excited each night, year after year, to go spend some time with his old friends, that is when I hear my passion and my words coming out of his mouth. I am a hopeless variable star addict like Leslie, having now submitted over 80,000 observations of my own to the AAVSO. Awards and accolades are great, but like Leslie, I would have done it all anyway. I don't think I really had a choice.

It is because of who this award is named for that it means so very much to me. I'd like to thank my wife, Irene, for supporting me and enabling my addiction. Thank you to the Astronomical League for this very special and meaningful recognition. And thank you, Leslie Peltier, for being an inspiration and role model for amateur astronomers everywhere who want to reach for the stars and explore the Universe on their own terms, in their own time and in their own way."